Hi there,

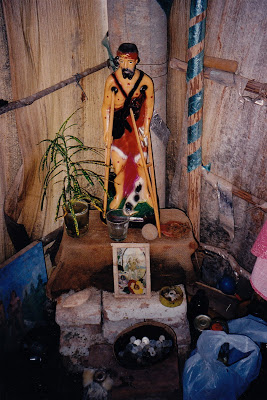

Today begins a couple of posts about santería and the purification ritual I had with a santera in the countryside outside Guardalavaca in north-eastern Cuba. This is a statue to Babablú-Ayé, otherwise known as Santo Lazaro or Saint Lazarus. I took it inside the shed where Isabel performs her rituals — with permission. I was alone and it was night, on my second of many visits to Isabel’s. She’s really quite remarkable, my window on the character of Sara in my first novel, The Phoenix Lottery.

To give you an idea of how fact and fiction work in the novel, here’s an excerpt that follows after another Phoenix Lottery excerpt that I posted about a week ago. It has a fairly concise description of the religion and its origins. (Voodoo in French-speaking Haiti and Louisiana.) Next post, I’ll have more pix and describe the ritual I underwent.

Cheers,

Allan.

********************

SANTERÍA

Sara has been at Xanadu for ten years, employed by duPont on the recommendation of the local schoolmaster. She lives in the village with her mother, husband and four children in a three-room house built of wood and tin. Every morning before dawn she bicycles out to the mansion. Here, with other servants, she tends to the kitchen, does light housekeeping, and makes the beds of late-sleeping guests.

A striking, literate woman with a wry smile, Sara is a descendent of Yoruban slaves. Rulers of the once-powerful kingdom of Benin, these Africans, from what is now southwest Nigeria, were brought to Central and South America by Spanish, Portuguese and French slave traders in the first half of the sixteenth century.

The Yoruba followed an animistic religion presided over by the one true God, Olofi. At the moment of creation, Olofi grew until He became so big it was impossible for Him to deal with the tiny problems of mere mortals. As a result, He created the orishas, a group of over four hundred sub-gods, each with a specific area of expertise. It is to these orishas that believers pray to this day, rather than to a preoccupied Almighty.

In this respect, the orishas function like Catholic saints, mediating between humankind and an all-powerful God. But unlike Catholic saints, the orishas were never living, breathing mortals. In a delicious irony, once-human Catholic saints embody notions of spiritual perfection, whereas the wholly ethereal orishas, like the gods of ancient Greece, are given to all manner of human foibles.

One of their appetites is for blood, particularly that of chickens and goats. Animal sacrifice was, and is, one of the primary payments to the orisha for the casting of a successful spell, and naturally compensation is important as sorcery is ultimately a business transaction between a willing god and a needy supplicant. Sacrifice is an easy sell, however, given the track record of the Yoruban gods in turning dreams to reality.

In any event, sixteenth century slave traders carrying their Yoruban captives to the Caribbean were understandably unnerved to discover that their human cargo was practising witchcraft below deck. They sought to stamp out the heathen practices. But the Yoruba camouflaged their faith by the simple expedient of adopting the religious forms of their Catholic masters. This was easily accomplished, given certain surface parallels between the two faiths. For instance, the Yoruba would hide dolls representing their orishas inside hollowed-out statues to Christian saints; and they would pray to their orishas using the names of these saints. The warrior god Changó was called forth by the name Santa Barbara; Babalú-Ayé, god of sickness and epidemic, was raised, appropriately enough, by calling upon Santa Lazarus; while the great god Oshún responded to prayers to Our Lady of Charity.

In time, African witchcraft and Christianity syncretized into Santería in Spanish speaking colonies such as Cuba and Puerto Rico. In the Portuguese colony of Brazil, the amalgam became recognized as Candomblé. Most famously, in the French colony of Haiti, it developed into Voodoo.

Santería is now so integrated in Latin culture that it numbers over one hundred million adherents throughout Latin America, with millions of other devotees belonging to its cousins Voodoo and Candomblé. Nor are these religions the preserve of the illiterate or outcast. Initiates include devout pillars of the community who attend Eucharist by day and animal sacrifice by night, a juxtaposition of rituals which should be readily understood by Catholic suburbanites; after all, the doctrine of transubstantiation, which claims communion bread and wine transform to the literal body and blood of Christ, turns orthodox believers into cannibals.

At least that is Sara’s view.

Determined to become a santera, a member of the Santerían priesthood, Sara has already gone through the initiation of Los Guerreros and is now an aleya in the eighth rank of her religion. She has seen much that Western eyes would scarcely credit. To her, it is beyond question that Junior has seen the Pillow Lady hiding in the chandelier. Let Western materialists think what they may, she knows the household is in need of a spell. She forgoes lunch, pedalling to the home of her spiritual leader, the babalawo at the corner of Avenida Tercera and Calle 48. She confers with him briefly, promising a chicken and a bottle of rum by week’s end, and returns to Xanadu in time to serve pre-dinner cocktails.

Emily is upstairs with Junior, distracting the boy with rousing Baptist hymns; a triumphant progression of big fat chords belted out in no-nonsense four-four time. Kitty considers Emily’s sing-alongs unspeakably déclassé, but there can be no denying their power to entertain the very young. What Baptists lack in subtlety, they make up in exuberance.

Meantime, Althea is holding forth in the library with a dry martini. “Our Joseph, may his soul rest in peace, was a war hero. He didn’t want to grow up to be a Christmas angel. He wanted to grow up to be a soldier!” With that, Althea sets her glass down firmly, serving notice that cocktail hour is over. She and Henry navigate their way upstairs to dress for dinner, leaving Edgar and Kitty to knock back a pitcher of Mojitos.

Sara seizes the initiative. “Forgive me, but I hear the little one cry. I see his eyes. He is in some danger, yes, for he is haunted by an Espíritu Intranquilo. You call that in English, I think, a Restless Spirit. Please, do not worry. I have seen the babalawo. All will be well. You make for your son a resguardo — a talisman, yes? To do this, you sew a small, white bag. In it put garlic, yerbabuena and perejil . Camphor also — evil spirits love their camphor. Sew this bag shut tight and dip it in the holy water of seven churches. The Espíritu Intranquilo who frightens your boy will go away.”

There is a pause. Kitty smiles graciously and says, “Thanks ever so much, Sara. I’m sure you’re trying to help, but that’s not how we do things in Ontario.”

Sara considers this. “You are right. I do not know the ways of Ontario.” She clears the sideboard and exits. Edgar leaves Kitty with the Mojitos and follows Sara to the kitchen, picking up a pencil and notepad en route.

“Sara, I’d like to have a word with you.”

“I am sorry if I interfere.”

“Not at all. About that talisman… Where can I find some perejil ?

Hi Allan: I expect you are enjoying your to Cuba. Just checking out your blog on the computer at Chester Village. Looking forward to seeing you soon.

Mom/Dorothy